Leverton Murder

By Glynda Pflug

G. W. Arrington

G. W. Arrington

The late 1890's brought change to the Panhandle of Texas. The Kiowas and Comanches were on reservations or had been run to other parts of the state. Cowmen, Spanish sheepmen, farmers, and merchants started moving into the wide-open Panhandle in earnest.

Center of population was Fort Elliot were 296 soldiers, families and civilians workers lived. Nearby, Mobeetie registered 166 citizens. Population in Moore County in 1890 was 15 residents. By 1900, it had grown to 209, but in the late 1880's the county was not organized and there was no law enforcement close. Mobeetie was the nearest and was the headquarters for law enforcement for Wheeler County and 14 attached counties in the unorganized Texas Panhandle.

Charles Goodnight brought one of the first herds of cattle and settled in the Panhandle in 1876. He became friends with Texas Ranger Captain G. W. Arrington. After the captain retired in 1882, Goodnight convinced him to run for sheriff at Mobeetie.

In Moore County, two brothers, George and John Leverton, and their families had received permission from LX foreman to run a hew head of cattle on LX grass and also had permission to live in an old ranch house in Evans Canyon in Southeast Moore County until the fall cattle drive was over.

When the drive was over and the ranch crew needed the cabin as a line shack for winter, the Levertons refused to leave. They claimed it was built on a school section and was state property. Rather than have trouble with the Levertons, the ranch crew spent the winter in a small rock house that had been used as a blacksmith shop. This was the beginning of trouble between the Leverton Brothers and the cattlemen.

During the spring roundup, cowboys rode into the valley where the brothers had some 250 cattle. After looking after the herd, the cowboys cut out three two-year-old steers claiming ownership. John Leverton protested, but lost the argument. The cowmen began to watch the Leverton Brothers carefully.

A Turkey Track cowboy named Ellington was riding into camp one evening and saw John and George driving a cow and a calf toward their Evans Canyon cabin. As the story goes, the cow had hoofs "like a goat's horns," and every cowmen in the Panhandle knew her part as part of the Turkey Track ranch. The Levertons threatened Ellington that if he mentioned what he had seen "his horse would come in without a rider."

Ellington continued to trail them. Because of the horn-like hooves, the cow could not travel fast and the calf finally got too tired to go on. The brothers tied the calf to a tree and went on. After dark, Ellington cut an "H" into the calf's hoof so it could be identified later. He reported to C. B. Willingham, his boss, what he had seen and Willingham immediately set out for Mobeetie to swear out a warrant for the arrest of the Levertons for rustling. Sheriff Arrington and his posse left for the Leverton cabin. The posse included Arrington, Willingham, Woods Coffee, Rube Hutton, Mack Sanford and T. N. Adams. They were about four miles from the cabin when dark came and they made camp for the night.

Center of population was Fort Elliot were 296 soldiers, families and civilians workers lived. Nearby, Mobeetie registered 166 citizens. Population in Moore County in 1890 was 15 residents. By 1900, it had grown to 209, but in the late 1880's the county was not organized and there was no law enforcement close. Mobeetie was the nearest and was the headquarters for law enforcement for Wheeler County and 14 attached counties in the unorganized Texas Panhandle.

Charles Goodnight brought one of the first herds of cattle and settled in the Panhandle in 1876. He became friends with Texas Ranger Captain G. W. Arrington. After the captain retired in 1882, Goodnight convinced him to run for sheriff at Mobeetie.

In Moore County, two brothers, George and John Leverton, and their families had received permission from LX foreman to run a hew head of cattle on LX grass and also had permission to live in an old ranch house in Evans Canyon in Southeast Moore County until the fall cattle drive was over.

When the drive was over and the ranch crew needed the cabin as a line shack for winter, the Levertons refused to leave. They claimed it was built on a school section and was state property. Rather than have trouble with the Levertons, the ranch crew spent the winter in a small rock house that had been used as a blacksmith shop. This was the beginning of trouble between the Leverton Brothers and the cattlemen.

During the spring roundup, cowboys rode into the valley where the brothers had some 250 cattle. After looking after the herd, the cowboys cut out three two-year-old steers claiming ownership. John Leverton protested, but lost the argument. The cowmen began to watch the Leverton Brothers carefully.

A Turkey Track cowboy named Ellington was riding into camp one evening and saw John and George driving a cow and a calf toward their Evans Canyon cabin. As the story goes, the cow had hoofs "like a goat's horns," and every cowmen in the Panhandle knew her part as part of the Turkey Track ranch. The Levertons threatened Ellington that if he mentioned what he had seen "his horse would come in without a rider."

Ellington continued to trail them. Because of the horn-like hooves, the cow could not travel fast and the calf finally got too tired to go on. The brothers tied the calf to a tree and went on. After dark, Ellington cut an "H" into the calf's hoof so it could be identified later. He reported to C. B. Willingham, his boss, what he had seen and Willingham immediately set out for Mobeetie to swear out a warrant for the arrest of the Levertons for rustling. Sheriff Arrington and his posse left for the Leverton cabin. The posse included Arrington, Willingham, Woods Coffee, Rube Hutton, Mack Sanford and T. N. Adams. They were about four miles from the cabin when dark came and they made camp for the night.

Leverton Cabin

Leverton Cabin

Just before dawn, George Leverton, unaware of the posse, gathered his dogs and headed to the nearby caprock to chase a panther he had heard during the night. The posse did not realize George had left the cabin.

A thin spiral of smoke came from the rock chimney as day broke. Light was flickering through the cabin window. Arrington slipped his 10-gauge shotgun made by Scott and Sons of Lubbock, Texas, (his favorite weapon) out of the boot. Others drew their six-shooters or Winchesters, climbed off their horses and walked quietly toward the cabin. Arrington cocked his shotgun and kicked in the door.

John was grinding cinnamon bark at the kitchen table. Mollie, his wife, was at the stove cooking breakfast. When the door flew open, John grabbed his pistol from a holster hanging on the end of the bed. He fired at Arrington who was first in the door. The bullet scorched Arrington's scarf, setting it on fire. Leverton fired again and the bullet ricocheted off the rock wall behind Arrington, hitting Willingham in the calf of his leg. Some stories say the bullet burned a scar across the cheek of the Leverton child lying in the crib, others say the child was on the bed.

Arrington fired, hitting Leverton in the shoulder, three of the pellets going completely through him. Arrington thought he had killed John, so he moved to the other room looking for George. John staggered to his feet and ran outside trying to get to a corn crib on the side of the house. Arrington hollered at him to stop.

Leverton, one arm dangling loose, turned and fired his pistol and kept on running.

Arrington yelled again for John to stop. John kept running and firing his pistol. Arrington fired again and John fell in the yard, 127 paces from the house. He died about four hours later.

A report in the Tascosa Pioneer by C. F. Rudolph, editor, headlined "Shot Thirteen Times." In the report, he stated that "Arrington read the warrant for Leverton's arrest after the man to be arrested was in a dying condition, shot thirteen times."

He referred to the posse and Arrington, "That an officer of the law could so far, forget his duty and his manhood, as to arm five deputies and then go beyond the line of his jurisdiction on an errand of deliberate and coldblooded murder seem incredible. But those who have had opportunity to know Arrington best pronounce his reputation in that direction an unsavory one as an officer."

Another Texas Ranger, Earl Vandale, wrote of the deed calling it clearly "a dastardly deed. By most people this killing was considered a cowardly uncalled for murder. John had heard they were going to get papers and arrest him. He sent word to Willingham that anytime he got papers for his arrest to send a man after him and he could come in. I think that is the truth, and there was no necessity of taking a strong posse to arrest one man."

Feelings ran high. Arrington expressed his feelings in a letter to the Tascosa Pioneer complaining of the language used in the report on the killing of John Leverton. Editor Rudolph backtracked slightly on his initial report.

Leverton's surviving relatives added to the drama by requesting protection from the Texas Rangers. A group of ten Rangers arrived to take charge of the unrest.

A thin spiral of smoke came from the rock chimney as day broke. Light was flickering through the cabin window. Arrington slipped his 10-gauge shotgun made by Scott and Sons of Lubbock, Texas, (his favorite weapon) out of the boot. Others drew their six-shooters or Winchesters, climbed off their horses and walked quietly toward the cabin. Arrington cocked his shotgun and kicked in the door.

John was grinding cinnamon bark at the kitchen table. Mollie, his wife, was at the stove cooking breakfast. When the door flew open, John grabbed his pistol from a holster hanging on the end of the bed. He fired at Arrington who was first in the door. The bullet scorched Arrington's scarf, setting it on fire. Leverton fired again and the bullet ricocheted off the rock wall behind Arrington, hitting Willingham in the calf of his leg. Some stories say the bullet burned a scar across the cheek of the Leverton child lying in the crib, others say the child was on the bed.

Arrington fired, hitting Leverton in the shoulder, three of the pellets going completely through him. Arrington thought he had killed John, so he moved to the other room looking for George. John staggered to his feet and ran outside trying to get to a corn crib on the side of the house. Arrington hollered at him to stop.

Leverton, one arm dangling loose, turned and fired his pistol and kept on running.

Arrington yelled again for John to stop. John kept running and firing his pistol. Arrington fired again and John fell in the yard, 127 paces from the house. He died about four hours later.

A report in the Tascosa Pioneer by C. F. Rudolph, editor, headlined "Shot Thirteen Times." In the report, he stated that "Arrington read the warrant for Leverton's arrest after the man to be arrested was in a dying condition, shot thirteen times."

He referred to the posse and Arrington, "That an officer of the law could so far, forget his duty and his manhood, as to arm five deputies and then go beyond the line of his jurisdiction on an errand of deliberate and coldblooded murder seem incredible. But those who have had opportunity to know Arrington best pronounce his reputation in that direction an unsavory one as an officer."

Another Texas Ranger, Earl Vandale, wrote of the deed calling it clearly "a dastardly deed. By most people this killing was considered a cowardly uncalled for murder. John had heard they were going to get papers and arrest him. He sent word to Willingham that anytime he got papers for his arrest to send a man after him and he could come in. I think that is the truth, and there was no necessity of taking a strong posse to arrest one man."

Feelings ran high. Arrington expressed his feelings in a letter to the Tascosa Pioneer complaining of the language used in the report on the killing of John Leverton. Editor Rudolph backtracked slightly on his initial report.

Leverton's surviving relatives added to the drama by requesting protection from the Texas Rangers. A group of ten Rangers arrived to take charge of the unrest.

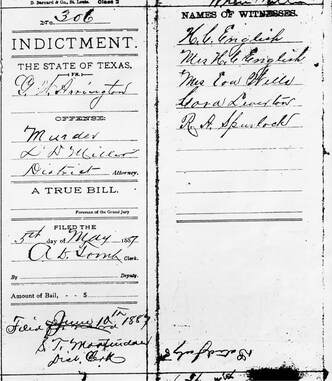

Arrington Court Papers

Arrington Court Papers

Arrington and Willingham testified before the grand jury in Tascosa on May 1, 1887. Woods Coffee, Rube Hutton, Mack Sanford, and T. N. Adams were also there. The four cowboys and Willingham were bound over, with a bond set at $200 each. Arrington's bond was set at $2,000. True bill #306 was filed against Arrington on May 5, 1887, by the Oldham County Grand Jury. Witnesses before the Grand Jury were W. C. English, Mrs. W. C. English (step-father and mother the Leverton Brothers), Mrs. Eva Walls, Cora Leverton, and R. A. Spurlock.

Because of the small population in some of the counties involved, a change of venue from Oldham County to Donly County was granted and the trial was held July 8, 1887 in the District Court there. Jurors were D. J. Murphy, Charles Goodnight (Arrington's good friend who helped him make Sheriff in Mobeetie), J. H. Parks, A. F. Perkins, W. M. Hildebrand, C. H. Taul, J. Shloss, J. H. Combs, Morris Rosenfield, J. E. Pickens, H. W. Taylor and Sam Dyer. Combs was foreman of the jury.

L. D. Miller was district attorney prosecuting the case. Defense attorneys were J. H. Woodman and B. M. Barker.

The trial was short and the verdict was brief -- "not guilty."

John Leverton was buried in the family graveyard in Evans Canyon. When construction of Lake Meredith began, the graves were moved to high ground at the mouth of Martin's Canyon. There were five graves at that time -- John, Mrs. William R. Leverton, Casinda Leverton, Mary Augusta Leverton and Billy Green, a young man who came to homestead in the area.

The family left the canyon for a time, but returned a few months later.

Widow Mollie Leverton later sold the Evans Canyon house to a family called Mann. Mollie had sold the house, but according to stories, she came back after she died.

The Manns didn't like their new visitor and sold the property to the Mastersons who didn't know about the ghost. They sold the property to the Osers who were the last to use the property before the lake covered it with water.

The Oser reportedly said Mollie looked in the window of the house at night when the wind howled. They sometimes found her in what had been the front room just standing were her husband had first been hit with the gunshots of the Sheriff.

After the Osers left, hunters and hikers in the canyon after dark are said to have reported a softly glowing white female apparition standing and waiting sometimes on the porch of the decaying house, sometimes inside.

In the summer of 1918, Mollie was seen several times. She didn't wail, she didn't moan. She just sobbed.

Compiled from Court Records from Oldham County, Donley County;

Newspaper reports from Moore County News-Press, Amarillo Daily News and Tascosa Pioneer;

from interviews with Woods Coffee Jr. (son of Woodson Coffee) and John Arrington (son of Sheriff Arrington);

from the Earl Vandale Papers in the University of Texas Archves, Austin;

and from other Panhandle historical reviews

Because of the small population in some of the counties involved, a change of venue from Oldham County to Donly County was granted and the trial was held July 8, 1887 in the District Court there. Jurors were D. J. Murphy, Charles Goodnight (Arrington's good friend who helped him make Sheriff in Mobeetie), J. H. Parks, A. F. Perkins, W. M. Hildebrand, C. H. Taul, J. Shloss, J. H. Combs, Morris Rosenfield, J. E. Pickens, H. W. Taylor and Sam Dyer. Combs was foreman of the jury.

L. D. Miller was district attorney prosecuting the case. Defense attorneys were J. H. Woodman and B. M. Barker.

The trial was short and the verdict was brief -- "not guilty."

John Leverton was buried in the family graveyard in Evans Canyon. When construction of Lake Meredith began, the graves were moved to high ground at the mouth of Martin's Canyon. There were five graves at that time -- John, Mrs. William R. Leverton, Casinda Leverton, Mary Augusta Leverton and Billy Green, a young man who came to homestead in the area.

The family left the canyon for a time, but returned a few months later.

Widow Mollie Leverton later sold the Evans Canyon house to a family called Mann. Mollie had sold the house, but according to stories, she came back after she died.

The Manns didn't like their new visitor and sold the property to the Mastersons who didn't know about the ghost. They sold the property to the Osers who were the last to use the property before the lake covered it with water.

The Oser reportedly said Mollie looked in the window of the house at night when the wind howled. They sometimes found her in what had been the front room just standing were her husband had first been hit with the gunshots of the Sheriff.

After the Osers left, hunters and hikers in the canyon after dark are said to have reported a softly glowing white female apparition standing and waiting sometimes on the porch of the decaying house, sometimes inside.

In the summer of 1918, Mollie was seen several times. She didn't wail, she didn't moan. She just sobbed.

Compiled from Court Records from Oldham County, Donley County;

Newspaper reports from Moore County News-Press, Amarillo Daily News and Tascosa Pioneer;

from interviews with Woods Coffee Jr. (son of Woodson Coffee) and John Arrington (son of Sheriff Arrington);

from the Earl Vandale Papers in the University of Texas Archves, Austin;

and from other Panhandle historical reviews