The Rest of the Story

By Glynda Pflug

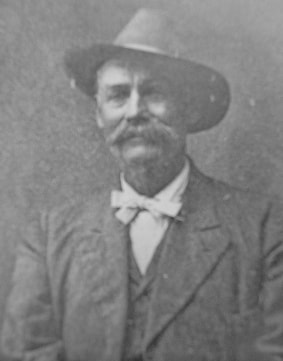

John R. Cook

John R. Cook

It's interesting what can be found in the archives at the Window on the Plains Museum.

One handwritten sentence on a piece of note paper led to a quest to find "the rest of the story."

One of the jobs Ezelle Fox held in Moore County was that of County Judge, but his favorite job was to be a historian. In the handwritten notes preparing for a talk he gave to the Rotary Club on November 18, 1959, he wrote, "John R. Cook relates his experiences in crossing the plains with some Mexican Buffalo hunters in 1874 in his book, The Border and the Buffalo. Cook is believed to be the first white man to come to Moore County."

This little bit of information led to the desire to know more about John R. Cook. A search of books in the museum library turned up a treasure. The Border and the Buffalo was a part of the library of Don Ray that is now in the museum library.

Cook left his home in Johnson County, Kansas, heading to Santa Fe, New Mexico. He formed a company of two other men and prospected for gold near Old Baldy. He talks about the "weird, almost human cries of distress" of the mountain lions and having to "chuck up" the campfire to keep the lions away from camp. The group searched for gold for several weeks, but found nothing of value. They "recovered from the gold fever" and dissolved the partnership.

The quest for gold had led him to Santa Fe. From there he went to Casa La Glorieta and in early October he started for the Panhandle of Texas.

He had become acquainted with Antonio Romero who, with his son, two sons-in-law and some neighbors were going on a "meat hunt." Cook was invited to join the group on the buffalo hunt.

Buffalo hunting was a new experience for Cook and he learned how to kill the buffalo, skin them and dry the hides. Some of the men in the party had guns, but Cook was taught how to use a lance to kill the buffalo. The group followed the herds of buffalo, adding to their supply of meat.

Cook was the only white man in the group and had no one to talk with. He wanted to join a group of white hunters, but had been unable to find any.

One morning, Romero asked to borrow Cook's Winchester to go looking for buffalo. About an hour later, one of the lancers told Cook about four white men who were camped about a mile away. "I had heard scarcely nothing but the Spanish lingo for more than five weeks, and was homesick for my own kind," so Cook left in search of the white men's camp.

"My earthly possessions at this time consisted of two pair of woolen blankets, one large, heavy, water-proof Navajo blanket, one bright, gaudy serape, a buffalo hair pillow, two suits of underclothes, two navy-blue over shirts, an extra pair of pants, an overcoat and an undercoat." He had $96.90 in his pocket and some identification papers.

Every horse was out of camp, so he left, walking, in search of the other camp. He left camp wearing "a half-worn pair of duck leggings." He expected to be gone no more than three or fours hours.

He followed a wagon trail down Blue Water to where it emptied into the South Canadian. He saw smoke across the river, and thinking that must be the camp, forded the river toward the smoke, finding only an abandoned camp.

He climbed to the top of the river bed and saw the outfit in the distance. Thinking he could catch them, he continued following them. At one point he heard the sound of a gun, so he turned and went that direction. He never found the group of white hunters, but instead decided to return to the Mexican camp.

One handwritten sentence on a piece of note paper led to a quest to find "the rest of the story."

One of the jobs Ezelle Fox held in Moore County was that of County Judge, but his favorite job was to be a historian. In the handwritten notes preparing for a talk he gave to the Rotary Club on November 18, 1959, he wrote, "John R. Cook relates his experiences in crossing the plains with some Mexican Buffalo hunters in 1874 in his book, The Border and the Buffalo. Cook is believed to be the first white man to come to Moore County."

This little bit of information led to the desire to know more about John R. Cook. A search of books in the museum library turned up a treasure. The Border and the Buffalo was a part of the library of Don Ray that is now in the museum library.

Cook left his home in Johnson County, Kansas, heading to Santa Fe, New Mexico. He formed a company of two other men and prospected for gold near Old Baldy. He talks about the "weird, almost human cries of distress" of the mountain lions and having to "chuck up" the campfire to keep the lions away from camp. The group searched for gold for several weeks, but found nothing of value. They "recovered from the gold fever" and dissolved the partnership.

The quest for gold had led him to Santa Fe. From there he went to Casa La Glorieta and in early October he started for the Panhandle of Texas.

He had become acquainted with Antonio Romero who, with his son, two sons-in-law and some neighbors were going on a "meat hunt." Cook was invited to join the group on the buffalo hunt.

Buffalo hunting was a new experience for Cook and he learned how to kill the buffalo, skin them and dry the hides. Some of the men in the party had guns, but Cook was taught how to use a lance to kill the buffalo. The group followed the herds of buffalo, adding to their supply of meat.

Cook was the only white man in the group and had no one to talk with. He wanted to join a group of white hunters, but had been unable to find any.

One morning, Romero asked to borrow Cook's Winchester to go looking for buffalo. About an hour later, one of the lancers told Cook about four white men who were camped about a mile away. "I had heard scarcely nothing but the Spanish lingo for more than five weeks, and was homesick for my own kind," so Cook left in search of the white men's camp.

"My earthly possessions at this time consisted of two pair of woolen blankets, one large, heavy, water-proof Navajo blanket, one bright, gaudy serape, a buffalo hair pillow, two suits of underclothes, two navy-blue over shirts, an extra pair of pants, an overcoat and an undercoat." He had $96.90 in his pocket and some identification papers.

Every horse was out of camp, so he left, walking, in search of the other camp. He left camp wearing "a half-worn pair of duck leggings." He expected to be gone no more than three or fours hours.

He followed a wagon trail down Blue Water to where it emptied into the South Canadian. He saw smoke across the river, and thinking that must be the camp, forded the river toward the smoke, finding only an abandoned camp.

He climbed to the top of the river bed and saw the outfit in the distance. Thinking he could catch them, he continued following them. At one point he heard the sound of a gun, so he turned and went that direction. He never found the group of white hunters, but instead decided to return to the Mexican camp.

"I will put the Panhandle of Texas against any other 180 square miles of territory in America for spasmodic, erratic weather."

-John R. Cook

At night, he had only the warmth of a campfire to keep him warm and was awakened during the night because the fire had gone down and he was cold.

He again followed a wagon trail in hopes of finding the Mexican camp. He came tot he breaks of the South Canadian and saw that the trail crossed it. The water was about three feet deep and with the help of a "sounding-stick" he made his way to a sand bar in the river. He walked out on the sand bar and his feet began to sink. He pulled his feet from the "quick sand," but in doing so lost his left shoe. He took the legging off his left foot and tied it "best I could" and headed to shelter under some cottonwood trees. He removed his clothing and hung them to dry and cleaned the sand from his stockings and remaining shoe.

"Hunger was gnawing at my vitals," Cook records. He would "upbraid myself for the lack of wisdom in leaving the Mexican camp without my gun or knife."

He was certain now that he would not find the white hunters or be able to return to the Mexican camp. He decided to follow the Canadian River toward Adobe Walls.

He had not journeyed far when the wind shifted to the northwest, blowing quite strong and soon snowflakes were falling. He began to look for shelter.

At one time, he thought he would be run over by a herd of antelope. "They were running at a rapid rate in the wake of the storm crossing the draw right at me, as it were, and before they were aware of my presence they were almost upon me, but discovered me just in time to separate, some jumping high, to the left and right, the entire band passing on each side of me. They came and were gone like the wind."

He found a deep ravine with an over jutting wall. Under the wall was a large pile of leaves. Cook used some logs left from a beaver dam and built a fire. He worked on making a moccasin for his foot, then climbed under the leaves to spend the night.

He was awakened during the night by the long-drawn-out howl of wolves. Here were two wolves facing him and he had no knife, no gun. He had heard about the effect of fire on wolves, so he grabbed two long logs from the fire and used them to keep the wolves away.

He continued waving the fire sticks as he continued walking along the river banks. He walked in a northeasterly direction in snow that was five inches deep. "The real pangs of hunger had left me, but weakness was creeping on."

A paragraph from Cook's book expresses his despair. "Right here I wish to stop this narrative long enough to say that I will put the Panhandle of Texas against any other 180 square miles of territory in America for spasmodic, erratic weather." As his journey continued, "the sun reached the meridian and it was very warm. Not a breath of air seemed to stir. The snow melted rapidly and before the middle of the afternoon it was a veritable slush; and I slowly spattered through it."

In order to keep warm, some nights he would build two fires and make his bed between them. In places where the river was shallow, it would be frozen in the morning.

He followed the river until he thought he saw tents across the river. He watched from the distance, then crossed the river to approach the camp. A man on a horse approached him. Cook told him, "Don't get uneasy, men; I'm all right. I've been lost."

Two other men got on each side of him and helped him to the camp. Cook's first question was "What place is this?" "It is Adobe Walls" was the response.

He was given food, a little coffee, one biscuit, a small piece of fried buffalo-meat and about two spoons-full of gravy. He told them he had not eaten for several days, but the lady who was caring for him said, "Now, we want you to have just all you can eat whenever we think you can stand it."

He was given clean clothes and water to wash with. Then he was introduced to the Buck Wood family. About 3 o'clock that afternoon, he laid down to sleep and slept for about sixteen hours.

Cook joined Buck Wood on his buffalo hunts and relates that at times the hides laid out to dry would cover the Plains for miles. He stayed with the Wood family and helped with buffalo hunts, telling the story of how he left New Mexico and crossed the Panhandle of Texas with just the clothes on his back, some matches and wearing one shoe.

During the time he was with the Wood family, the first wedding in the Panhandle took place at Fort Elliott. One of the Wood daughters, Virginia, married George Simpson, one of the men working for Buck Wood. They had ridden to the fort and were married by the post adjutant.

Cook was married later in life to Alice Victoria Maddux and they lived in the Dakota Territory for a time. During one of the times Cook was away from home on a hunting trip, Alice was the victim of The Great Blizzard of 1888. She laid in a snow drift for over 40 hours. Her feet were badly frozen and both had to be partly amputated. She suffered from "chilblains" and was never in good health again.

The couple had no children, but took in a 4-year old orphan child of a Confederate soldier. They adopted the boy, John Nelson Crump, but did not change his name.

In 1906, Cook returned to Kansas where he died in 1917. He is buried in the cemetery of Kansas Soldiers Home at Fort Dodge.

He again followed a wagon trail in hopes of finding the Mexican camp. He came tot he breaks of the South Canadian and saw that the trail crossed it. The water was about three feet deep and with the help of a "sounding-stick" he made his way to a sand bar in the river. He walked out on the sand bar and his feet began to sink. He pulled his feet from the "quick sand," but in doing so lost his left shoe. He took the legging off his left foot and tied it "best I could" and headed to shelter under some cottonwood trees. He removed his clothing and hung them to dry and cleaned the sand from his stockings and remaining shoe.

"Hunger was gnawing at my vitals," Cook records. He would "upbraid myself for the lack of wisdom in leaving the Mexican camp without my gun or knife."

He was certain now that he would not find the white hunters or be able to return to the Mexican camp. He decided to follow the Canadian River toward Adobe Walls.

He had not journeyed far when the wind shifted to the northwest, blowing quite strong and soon snowflakes were falling. He began to look for shelter.

At one time, he thought he would be run over by a herd of antelope. "They were running at a rapid rate in the wake of the storm crossing the draw right at me, as it were, and before they were aware of my presence they were almost upon me, but discovered me just in time to separate, some jumping high, to the left and right, the entire band passing on each side of me. They came and were gone like the wind."

He found a deep ravine with an over jutting wall. Under the wall was a large pile of leaves. Cook used some logs left from a beaver dam and built a fire. He worked on making a moccasin for his foot, then climbed under the leaves to spend the night.

He was awakened during the night by the long-drawn-out howl of wolves. Here were two wolves facing him and he had no knife, no gun. He had heard about the effect of fire on wolves, so he grabbed two long logs from the fire and used them to keep the wolves away.

He continued waving the fire sticks as he continued walking along the river banks. He walked in a northeasterly direction in snow that was five inches deep. "The real pangs of hunger had left me, but weakness was creeping on."

A paragraph from Cook's book expresses his despair. "Right here I wish to stop this narrative long enough to say that I will put the Panhandle of Texas against any other 180 square miles of territory in America for spasmodic, erratic weather." As his journey continued, "the sun reached the meridian and it was very warm. Not a breath of air seemed to stir. The snow melted rapidly and before the middle of the afternoon it was a veritable slush; and I slowly spattered through it."

In order to keep warm, some nights he would build two fires and make his bed between them. In places where the river was shallow, it would be frozen in the morning.

He followed the river until he thought he saw tents across the river. He watched from the distance, then crossed the river to approach the camp. A man on a horse approached him. Cook told him, "Don't get uneasy, men; I'm all right. I've been lost."

Two other men got on each side of him and helped him to the camp. Cook's first question was "What place is this?" "It is Adobe Walls" was the response.

He was given food, a little coffee, one biscuit, a small piece of fried buffalo-meat and about two spoons-full of gravy. He told them he had not eaten for several days, but the lady who was caring for him said, "Now, we want you to have just all you can eat whenever we think you can stand it."

He was given clean clothes and water to wash with. Then he was introduced to the Buck Wood family. About 3 o'clock that afternoon, he laid down to sleep and slept for about sixteen hours.

Cook joined Buck Wood on his buffalo hunts and relates that at times the hides laid out to dry would cover the Plains for miles. He stayed with the Wood family and helped with buffalo hunts, telling the story of how he left New Mexico and crossed the Panhandle of Texas with just the clothes on his back, some matches and wearing one shoe.

During the time he was with the Wood family, the first wedding in the Panhandle took place at Fort Elliott. One of the Wood daughters, Virginia, married George Simpson, one of the men working for Buck Wood. They had ridden to the fort and were married by the post adjutant.

Cook was married later in life to Alice Victoria Maddux and they lived in the Dakota Territory for a time. During one of the times Cook was away from home on a hunting trip, Alice was the victim of The Great Blizzard of 1888. She laid in a snow drift for over 40 hours. Her feet were badly frozen and both had to be partly amputated. She suffered from "chilblains" and was never in good health again.

The couple had no children, but took in a 4-year old orphan child of a Confederate soldier. They adopted the boy, John Nelson Crump, but did not change his name.

In 1906, Cook returned to Kansas where he died in 1917. He is buried in the cemetery of Kansas Soldiers Home at Fort Dodge.