1865 Drift Fence Caused Problems

By Glynda Pflug

Weathermen have been describing the freezing weather lately (2020) as the worst in 135 years. That would be the winter of 1865 when blowing snow and freezing temperatures covered the state of Texas and much of the surrounding states.

Weather stations recorded the lowest temperatures ever.

According to historians, there were about 250,000 cattle on ranges in Western Kansas, the Indian Territory and the Texas Panhandle. As the storm grew, the cattle bunched up for protection, then began to drift southward, seeking shelter.

Weather stations recorded the lowest temperatures ever.

According to historians, there were about 250,000 cattle on ranges in Western Kansas, the Indian Territory and the Texas Panhandle. As the storm grew, the cattle bunched up for protection, then began to drift southward, seeking shelter.

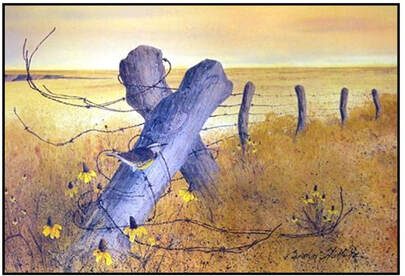

Painting of the drift fence by Carolyn Stallwitz

Painting of the drift fence by Carolyn Stallwitz

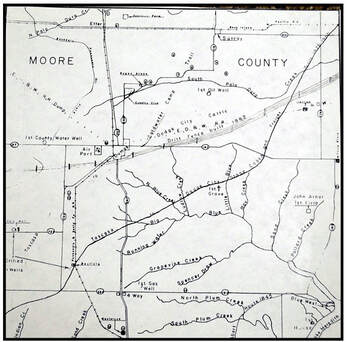

Ranchers, in an effort to protect their ranchlands had joined forces in the Panhandle Stock Association in 1862 and started building a fence across the Panhandle. The fence started in the breaks of New Mexico (about 35 miles from the Texas border) and ran east through the center of Hartley and Moore counties and then in a northeasterly direction to the border of Texas and Indian Territory (now Oklahoma). According to a newspaper clipping form November 6, 1884, it was the longest line of fencing in the world. Its purpose was to stop drifting cattle. It was completed in 1865.

The fence was constructed of posts, gathered from the Canadian River area, placed every thirty feet with gates every three miles. It was strung with Burnell Four-Point wire. Some references say there were four strands, others say five strands. The 65 wagon loads of wire and part of the posts were freighted from Dodge City, Kansas, on wagons pulled by teams of six to twelve horses.

The fence did what it was supposed to, but was the reason some cattlemen went bankrupt. When the cattle reached the fence, there was no place for them to go, so they stood with their backs to the wind and blowing snow and froze to death. The dead cattle were stacked so high along the fence that cattle that followed were able to climb over the frozen carcasses and reach the other side of the fence. After the storm, cattle covered the ground for a quarter of mile on each side of the fence.

The fence was constructed of posts, gathered from the Canadian River area, placed every thirty feet with gates every three miles. It was strung with Burnell Four-Point wire. Some references say there were four strands, others say five strands. The 65 wagon loads of wire and part of the posts were freighted from Dodge City, Kansas, on wagons pulled by teams of six to twelve horses.

The fence did what it was supposed to, but was the reason some cattlemen went bankrupt. When the cattle reached the fence, there was no place for them to go, so they stood with their backs to the wind and blowing snow and froze to death. The dead cattle were stacked so high along the fence that cattle that followed were able to climb over the frozen carcasses and reach the other side of the fence. After the storm, cattle covered the ground for a quarter of mile on each side of the fence.

Burnell Four-Point Barbed Wire

Burnell Four-Point Barbed Wire

Stories by "old-timers" told of being able to walk across the Panhandle on the backs of dead cattle, never touching the ground. Estimates were that 150,000 to 200,000 cattle died along the fence. These numbers do not include the cattle who died on the open ranges south of the fence.

John Hollicut, manager of the LX ranch in Potter and Moore counties, said cowboys lifted hides from 250 cattle per mile for thirty miles along one section of the Panhandle drift fence. The Texas Cattle Raisers Association asked cattlemen to deliver hides to Dodge City where an estimate could be made of the loss. By June 1, 1886, more than 400,000 hides were delivered and it was thought there might be thousands more decomposing on the plains.

A state law passed in 1889 prohibited any fence from crossing or enclosing public property. In compliance with this law, most of the fence was removed in 1890.

A historical marker stands on the south edge of Dumas to mark the crossing of the drift fence. Some maps show the trail actually crossed Window on the Plains Museum property. A display of barbed wire at Window on the Plains Museum includes a sample of the Burnell Four-Point wire.

John Hollicut, manager of the LX ranch in Potter and Moore counties, said cowboys lifted hides from 250 cattle per mile for thirty miles along one section of the Panhandle drift fence. The Texas Cattle Raisers Association asked cattlemen to deliver hides to Dodge City where an estimate could be made of the loss. By June 1, 1886, more than 400,000 hides were delivered and it was thought there might be thousands more decomposing on the plains.

A state law passed in 1889 prohibited any fence from crossing or enclosing public property. In compliance with this law, most of the fence was removed in 1890.

A historical marker stands on the south edge of Dumas to mark the crossing of the drift fence. Some maps show the trail actually crossed Window on the Plains Museum property. A display of barbed wire at Window on the Plains Museum includes a sample of the Burnell Four-Point wire.