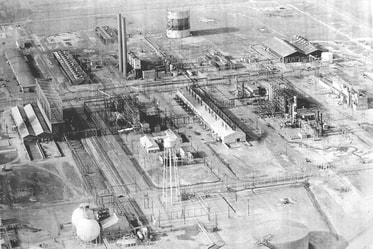

Cactus Ordinance Plant

By Glynda Pflug

Before the United States entered World War II, the government was building plants for war production over the nation.

In April 1941, Moore County received a telegram from Congressman Eugene Worley reporting a contract with Chemical Construction Company of New York to build, equip, and staff a manufacturing plant in Moore County.

The contract was for $5,000,000 and construction was to be supervised by the U.S. Corp of Engineers, the Denison, Texas, district.

Information was kept secretive and details were few, since it was a wartime project.

Some 700 acres of land along the two railroads north of Dumas were obtained, surveying was underway and drilling of water wells began.

The abundance of cheap natural gas, water at a depth of 350 feet and the crossing of two railroads made Cactus the perfect site for the production of ammonia with the probable use in making munitions. Ammonia is a product of natural gas, plus air and water. The plant was to be called the Cactus Ordnance Works.

U.S. Engineers were given offices on the second and third floor of the Moore County courthouse. They laid out plans for worker houses - 35 staff houses, five 63-man dormitories, two womens' dormitories, 75 two-family duplexes. a cafeteria, canteen, fire station, and other equipment that made an instant city - Cactus.

One Cactus resident recalls, "When I came out to interview for the job being offered, I took one look at the community and plant and was strongly tempted to turn and run in the other direction. It was quite unprepossessing. The housing area consisted of square, unpainted apartment buildings plus a few old army barracks that had been converted into apartments for the management personnel."

"When I left, I said 'I'll let your know', but I never intended coming back. But the best laid plans of mice and men oft go aglee." He went on to say that the salary was good, but more importantly they offered housing which was almost impossible to find, especially with a small child. He took the job and grew to appreciate the people and the community.

The project promised to bring in as many people as Moore County already had living there.

By August, there was a formal flag raising at the newly-designed Cactus Ordnance Works.

Employment was reported to be between 2,000 and 3,000 people with 85 percent of those signing up for war bond purchases by payroll deduction.

Things quickly changed May 5, 1943 when word came from Washington to liquidate the plant. It was only 85 percent completed, but Washington explained that the plant was intended as a standby measure in the war munitions program and that the changing course of the war indicated that this reserve would not be needed.

Brown and Root, the contractor building the plant, began shutting down. U.S. Engineers began removing machinery. Three of the four units erected to make ammonia were dismantled and shipped to other plants manufacturing other war materials.

Chemical Construction argued that the plant was too valuable to close and had a great potential for providing vital chemicals. In mid-June 1943, Shell Chemical Company of San Francisco visited the plant and in July, a coalition was formed between Shell and Chemical Construction.

Work started again, but this time the plant was to be for the production of a gasoline additive for aviation fuel by a process Shell Chemical had developed. Production of the additive began in February 1944. Production of the additive was for only a few months, then the plant was converted back to ammonia. By this time, Japan had surrendered and the plant was closing.

The industry was a big part of the county's economy and county officials worked hard to keep it operating.

Shell negotiated unsuccessfully to acquire the plant as government surplus. On November 24, 1945, the last Shell employee left and the plant was shutdown.

In June of the following year, the plant was taken off the government surplus list and postwar activities began breathing life into it.

War-torn countries needed nitrogen fertilizers to restore farm production.

Emergency Export Corp, a subsidiary of Spence Chemical Company of New York, began production of ammonium nitrate. The government wanted 70,000 tons from the Cactus plant. This amount was half of the existing U.S. production of ammonium nitrate.

The Cactus plant produced 250 tons daily and employed 375 people. The fertilizer was credited with boosting European grain production and alleviating world hunger.

The anhydrous ammonia was produced in three phases. The first was in Cactus where liquid ammonia was shipped in tank cars to a plant in Sunflower, KS, where the ammonia was oxidized at a nitric acid plant and the product becomes ammonium nitrate. The product was then shipped by rail to another plant on the west coast where it was converted to anhydrous ammonia which looked like a yellow granulated sugar. It was them mixed with paraffin, rosin, and clay to make it usable with farmer's drills.

A fire in March of 1948 destroyed much of the plant, but it was rebuilt.

A lease was worked out with Phillips Chemical, a division of Phillips Petroleum Company, who eventually purchased the plant and leased the housing area.

Employment stabilized at about 600 and by the end of the 1950's, the plant was updated and automated.

Increasing competition in fertilizer production caused the plant's employment to drop to around 200 by the late 1960's.

In November 1973, the ammonia section, the plant's largest production unit, was shut down. The nitric acid and ammonium nitrate were still manufactured, but by the early 1980's, the plant was completely shut down.

Compiled from: information in the archives at Window on the Plains Museum

"Our One and Only Cactus" by Funk and Futrell

"100 Moore Years"

In April 1941, Moore County received a telegram from Congressman Eugene Worley reporting a contract with Chemical Construction Company of New York to build, equip, and staff a manufacturing plant in Moore County.

The contract was for $5,000,000 and construction was to be supervised by the U.S. Corp of Engineers, the Denison, Texas, district.

Information was kept secretive and details were few, since it was a wartime project.

Some 700 acres of land along the two railroads north of Dumas were obtained, surveying was underway and drilling of water wells began.

The abundance of cheap natural gas, water at a depth of 350 feet and the crossing of two railroads made Cactus the perfect site for the production of ammonia with the probable use in making munitions. Ammonia is a product of natural gas, plus air and water. The plant was to be called the Cactus Ordnance Works.

U.S. Engineers were given offices on the second and third floor of the Moore County courthouse. They laid out plans for worker houses - 35 staff houses, five 63-man dormitories, two womens' dormitories, 75 two-family duplexes. a cafeteria, canteen, fire station, and other equipment that made an instant city - Cactus.

One Cactus resident recalls, "When I came out to interview for the job being offered, I took one look at the community and plant and was strongly tempted to turn and run in the other direction. It was quite unprepossessing. The housing area consisted of square, unpainted apartment buildings plus a few old army barracks that had been converted into apartments for the management personnel."

"When I left, I said 'I'll let your know', but I never intended coming back. But the best laid plans of mice and men oft go aglee." He went on to say that the salary was good, but more importantly they offered housing which was almost impossible to find, especially with a small child. He took the job and grew to appreciate the people and the community.

The project promised to bring in as many people as Moore County already had living there.

By August, there was a formal flag raising at the newly-designed Cactus Ordnance Works.

Employment was reported to be between 2,000 and 3,000 people with 85 percent of those signing up for war bond purchases by payroll deduction.

Things quickly changed May 5, 1943 when word came from Washington to liquidate the plant. It was only 85 percent completed, but Washington explained that the plant was intended as a standby measure in the war munitions program and that the changing course of the war indicated that this reserve would not be needed.

Brown and Root, the contractor building the plant, began shutting down. U.S. Engineers began removing machinery. Three of the four units erected to make ammonia were dismantled and shipped to other plants manufacturing other war materials.

Chemical Construction argued that the plant was too valuable to close and had a great potential for providing vital chemicals. In mid-June 1943, Shell Chemical Company of San Francisco visited the plant and in July, a coalition was formed between Shell and Chemical Construction.

Work started again, but this time the plant was to be for the production of a gasoline additive for aviation fuel by a process Shell Chemical had developed. Production of the additive began in February 1944. Production of the additive was for only a few months, then the plant was converted back to ammonia. By this time, Japan had surrendered and the plant was closing.

The industry was a big part of the county's economy and county officials worked hard to keep it operating.

Shell negotiated unsuccessfully to acquire the plant as government surplus. On November 24, 1945, the last Shell employee left and the plant was shutdown.

In June of the following year, the plant was taken off the government surplus list and postwar activities began breathing life into it.

War-torn countries needed nitrogen fertilizers to restore farm production.

Emergency Export Corp, a subsidiary of Spence Chemical Company of New York, began production of ammonium nitrate. The government wanted 70,000 tons from the Cactus plant. This amount was half of the existing U.S. production of ammonium nitrate.

The Cactus plant produced 250 tons daily and employed 375 people. The fertilizer was credited with boosting European grain production and alleviating world hunger.

The anhydrous ammonia was produced in three phases. The first was in Cactus where liquid ammonia was shipped in tank cars to a plant in Sunflower, KS, where the ammonia was oxidized at a nitric acid plant and the product becomes ammonium nitrate. The product was then shipped by rail to another plant on the west coast where it was converted to anhydrous ammonia which looked like a yellow granulated sugar. It was them mixed with paraffin, rosin, and clay to make it usable with farmer's drills.

A fire in March of 1948 destroyed much of the plant, but it was rebuilt.

A lease was worked out with Phillips Chemical, a division of Phillips Petroleum Company, who eventually purchased the plant and leased the housing area.

Employment stabilized at about 600 and by the end of the 1950's, the plant was updated and automated.

Increasing competition in fertilizer production caused the plant's employment to drop to around 200 by the late 1960's.

In November 1973, the ammonia section, the plant's largest production unit, was shut down. The nitric acid and ammonium nitrate were still manufactured, but by the early 1980's, the plant was completely shut down.

Compiled from: information in the archives at Window on the Plains Museum

"Our One and Only Cactus" by Funk and Futrell

"100 Moore Years"