Antique Bottles Found in City Dump

The county courthouse was constructed in the early 1930's and the top floor was built to house the jail as well as an apartment for the county sheriff.

In 1979, county commissioners realized the need for a larger facility for the jail and offices.

When excavation started on the northeast corner of the courthouse square, county crews moved out about 300 dump truck loads of dirt, making a swimming-pool sized hole 13 feet deep, 90 feet wide and 51 feet long. During the excavation, treasures started appearing in the piles of dirt. At least the items were treasures to collectors of old bottles like W. D. Bales, county roads supervisor, who was overseeing the county work on the new building.

Bales rescued six of the old bottles, but several were crushed by the earth-moving machinery. Others were probably lost in the massive piles of dirt that became the foundation for the building.

"These were all different from bottles I've seen in antique shops," he reported in a newspaper story in April of that year. "Most don't have names or dates, but all are imperfect with air bottles in the glass. They must be patent medicine bottles."

As late as the 1930's, that corner of the square was used as a trash burning pit, according to several longtime Dumas residents. In the News-Press story, Collier Phillips remembered, "When I was a boy, everyone in the city -- residents and businesses, burned trash on premises and dumped it in the pits."

In 1979, county commissioners realized the need for a larger facility for the jail and offices.

When excavation started on the northeast corner of the courthouse square, county crews moved out about 300 dump truck loads of dirt, making a swimming-pool sized hole 13 feet deep, 90 feet wide and 51 feet long. During the excavation, treasures started appearing in the piles of dirt. At least the items were treasures to collectors of old bottles like W. D. Bales, county roads supervisor, who was overseeing the county work on the new building.

Bales rescued six of the old bottles, but several were crushed by the earth-moving machinery. Others were probably lost in the massive piles of dirt that became the foundation for the building.

"These were all different from bottles I've seen in antique shops," he reported in a newspaper story in April of that year. "Most don't have names or dates, but all are imperfect with air bottles in the glass. They must be patent medicine bottles."

As late as the 1930's, that corner of the square was used as a trash burning pit, according to several longtime Dumas residents. In the News-Press story, Collier Phillips remembered, "When I was a boy, everyone in the city -- residents and businesses, burned trash on premises and dumped it in the pits."

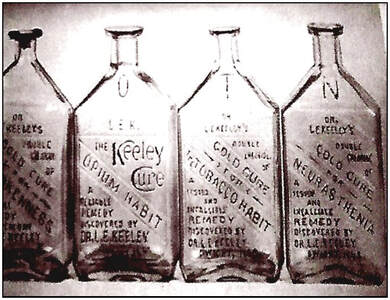

Dr. L. E. Keeley's Infallible remedies

Dr. L. E. Keeley's Infallible remedies

The prize bottle according to Bales was a patent medicine bottle that contained Dr. L. E. Keeley's "infallible remedy -- A Double Chloride of Gold Cure of the Tobacco Habit."

The bottle came from a company in Dwight, Illinois, operated by Dr. Keeley, and partners, a chemist and town mayor. They ran a sanitarium for those addicted to alcohol or opium.

He offered a tonic whose secret formula supposedly included bichloride of gold. He also gave hypodermic injections. He promised a 95% cure rate.

An analysis showed the product contained no gold.

Instead, the tonic was nearly 28% alcohol and contained ammonium chloride, tincture of cinchona (the bark from which quinine is made) and aloin (a compound obtained from the aloe plant).

The injections contained strychnine and boric acid (both otherwise used as insecticides) and atropine (another poison).

Other similar treatments in other parts of the country claimed to include gold treatments, but an analysis did not show gold. The treatments were short-lived, but the developers of the programs died wealthy men.

Compiled from: Moore County News-Press story, April 1979

The bottle came from a company in Dwight, Illinois, operated by Dr. Keeley, and partners, a chemist and town mayor. They ran a sanitarium for those addicted to alcohol or opium.

He offered a tonic whose secret formula supposedly included bichloride of gold. He also gave hypodermic injections. He promised a 95% cure rate.

An analysis showed the product contained no gold.

Instead, the tonic was nearly 28% alcohol and contained ammonium chloride, tincture of cinchona (the bark from which quinine is made) and aloin (a compound obtained from the aloe plant).

The injections contained strychnine and boric acid (both otherwise used as insecticides) and atropine (another poison).

Other similar treatments in other parts of the country claimed to include gold treatments, but an analysis did not show gold. The treatments were short-lived, but the developers of the programs died wealthy men.

Compiled from: Moore County News-Press story, April 1979