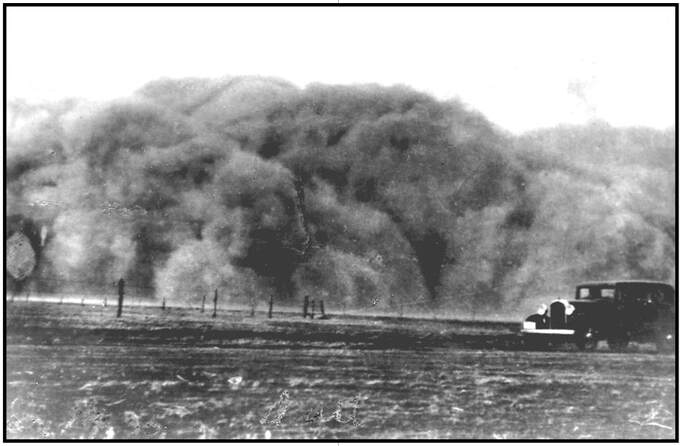

1935 Dust Storms

Delbert Lewis

Delbert Lewis

A story in Window on the Plains archives was written by Delbert Lewis about the 1935 Dust Storm. He remembers the storms from a child's view point, but written after he was older.

He titled it "1935 Dust Storms".

"By Marth 24th, southwestern Colorado, the Texas Panhandle, and western Kansas had experience twelve consecutive days of dust storms. But worse was on the way! In March a new cold-front-driven sand storm swept across the plains destroying everything. An unbelievable one-half of the wheat crop in Kansas, one-quarter of it in Oklahoma, and all of it in Nebraska. Five million acres blown out! A staggering loss to an already crippled farm economy."

"The Amarillo Daily News, April 10, 1935, puts things into a more personal perspective. "Dust, driven by 40-mph wind, caused the closing of schools in Boise City, Oklahoma. Travel in Liberal, Kansas, was at a virtual standstill. The dust storm at Lubbock, Texas was one of the worst in that city's history. At Guymon, Oklahoma, the dust...raging for 48 hours reached a climax late in the day spreading more damage. Southwest winds carried the dust through Amarillo, cutting visibility to less than one-eighth mile. Motorists turned on headlights in an effort to see through the haze."

Just about the time area residents were ready to give up hope for rain. Amarillo explosives expert Tex Thornton, a personal friend of my Dad (H. D. Lewis) from the 1920's oil field days in the Panhandle, agreed to go to Dalhart, one of the worst drought-ridden areas in the Panhandle, to 'make-rain'. But even as Thornton set off a blast every 20 minutes the dust drove the crowd of on-lookers to their cars. He finally gave up."

"In Boise City, Oklahoma, the epicenter of the Dust Bowl, the local paper quoted Cimarron County Agent William "Uncle Bill" Barker that wheat production back in 1925 had been almost 6,000,000 bushels with a comfortable yield of 21.7 bushels per acre. Through all the 1920's, production averaged a comfortable 13.1 bushels. In the 1930's. it was less than one pathetic bushel per acre. Of 250,000 acres planted in the fall of 1936, "not a head of wheat matured in the entire county in 1937," he said. An economic loss so stupefying as to defy description. Then the wind slackened off a bit, gathering strength, as it were, for the spectacular of that appalling spring."

"April 14, 1935 was the storm of the century. This was a destructive genuine double-bitch of a storm that came crashing down on us. The one storm to never forget."

"Sunday morning was a clear and springy day all across the Panhandle. After church the skies were a clear blue so that we children played outside while mother caught up on some inside work. In late afternoon the quiet-still air was mild and warm and bright. Mary, Martha, and I were playing under the water tower (erected in 1924 and disassembled in 1956) at Second and Porter Streets."

"Then, slowly all across the northern sky a rising dirt cloud floated up from the north lifting up and around to the east and west all along the horizon. Mary and Martha and I knew exactly what was in store, but we were playing with no thought to call Mother. We continued on in childish abandon gathering "grab a root and growls" for the supper table, a yellow flower we had named for its root system. By now we were used to these storms, we thought, and decided to "tough it out" until the storm fully descended. But when it did, it did it with a capital D!"

He titled it "1935 Dust Storms".

"By Marth 24th, southwestern Colorado, the Texas Panhandle, and western Kansas had experience twelve consecutive days of dust storms. But worse was on the way! In March a new cold-front-driven sand storm swept across the plains destroying everything. An unbelievable one-half of the wheat crop in Kansas, one-quarter of it in Oklahoma, and all of it in Nebraska. Five million acres blown out! A staggering loss to an already crippled farm economy."

"The Amarillo Daily News, April 10, 1935, puts things into a more personal perspective. "Dust, driven by 40-mph wind, caused the closing of schools in Boise City, Oklahoma. Travel in Liberal, Kansas, was at a virtual standstill. The dust storm at Lubbock, Texas was one of the worst in that city's history. At Guymon, Oklahoma, the dust...raging for 48 hours reached a climax late in the day spreading more damage. Southwest winds carried the dust through Amarillo, cutting visibility to less than one-eighth mile. Motorists turned on headlights in an effort to see through the haze."

Just about the time area residents were ready to give up hope for rain. Amarillo explosives expert Tex Thornton, a personal friend of my Dad (H. D. Lewis) from the 1920's oil field days in the Panhandle, agreed to go to Dalhart, one of the worst drought-ridden areas in the Panhandle, to 'make-rain'. But even as Thornton set off a blast every 20 minutes the dust drove the crowd of on-lookers to their cars. He finally gave up."

"In Boise City, Oklahoma, the epicenter of the Dust Bowl, the local paper quoted Cimarron County Agent William "Uncle Bill" Barker that wheat production back in 1925 had been almost 6,000,000 bushels with a comfortable yield of 21.7 bushels per acre. Through all the 1920's, production averaged a comfortable 13.1 bushels. In the 1930's. it was less than one pathetic bushel per acre. Of 250,000 acres planted in the fall of 1936, "not a head of wheat matured in the entire county in 1937," he said. An economic loss so stupefying as to defy description. Then the wind slackened off a bit, gathering strength, as it were, for the spectacular of that appalling spring."

"April 14, 1935 was the storm of the century. This was a destructive genuine double-bitch of a storm that came crashing down on us. The one storm to never forget."

"Sunday morning was a clear and springy day all across the Panhandle. After church the skies were a clear blue so that we children played outside while mother caught up on some inside work. In late afternoon the quiet-still air was mild and warm and bright. Mary, Martha, and I were playing under the water tower (erected in 1924 and disassembled in 1956) at Second and Porter Streets."

"Then, slowly all across the northern sky a rising dirt cloud floated up from the north lifting up and around to the east and west all along the horizon. Mary and Martha and I knew exactly what was in store, but we were playing with no thought to call Mother. We continued on in childish abandon gathering "grab a root and growls" for the supper table, a yellow flower we had named for its root system. By now we were used to these storms, we thought, and decided to "tough it out" until the storm fully descended. But when it did, it did it with a capital D!"

"Again the Amarillo Daily News lucidly describes the storm: " Black Sunday...The dust peaked...turning day into night... blotting out every speck of light, the worst dust storm in the history of the Panhandle covered the entire region. The billowing black cloud struck... and visibility was zero... darkness settled swiftly after the city had been enveloped in the stinking dust... despite closed windows and doors, the silt crept into buildings... within two hours the dust was a quarter of an inch in thickness in homes and stores. And this author will testify at the Pearly Gates that this report was a conservative observation. Twenty storms were thus reported during March that year, and by the middle of April, the High Plains had endured 10 more."

"These storms rolled serenely out of the north, the cold winds sliding under the warmer air, lifting up the turbulent face of the storm in huge cloud-like rolls, until they hit. This one did too! It came as soundlessly as a ghost, as relentless as death until its towering dust overrode us."

"As it silently covered the sky curling south, we "chickened out" and ran for cover, but by then we were "gone goslings". In that one instant it overwhelmed two little six year old girls and one eight year old boy and tumbled us along with the surging tumbleweeds. With our eyes muddied shut we barely found the porch steps before everything went solid black. Mother saw the afternoon light suddenly go dark and knew instantly what had us. She hit the porch light and came out, but she was as mad as an old wet hen, we hadn't the wisdom to come in ahead of the storm and she made Attila the Hun seem like Mary Magdalene. I understand now, her fear she couldn't find us in the dust, and she couldn't have."

"A few of our little friends couldn't find their homes in the dust so they just "stayed put 'till" the next day. My sister Mary remembers, as was usual, when some such catastrophe struck Daddy would be off on some eleemosynary mission. This time it was to Washington D. C. with several other Moore County farmers to plead with the Federal Government to stop foreclosing farm mortgages. Actually, my Dad, County Judge Noel McDade, and a couple of other farmer were astonishingly successful in their testimony and saved many a farmer from ruin."

"After 1935, the dust storms lost their drama for us children. We'd seen all that nature could throw. The storms were simply a burden to bare and bare it we did, but sometimes that burden was just about all we could bare. We though the whole world was like this and children everywhere simply lived with the environment."

"The plains people, however, then as now, were a tough minded, leather skinned bunch of prairie dogs. And not easily driven off. Even in 1935 we managed to laugh a bit at our misfortunes. The grown-ups told about the fellow who fainted when a drop of water struck him in the face and had to be revived by having a bucket of sand thrown over him. They also told the one about the motorist who came upon a ten-gallon hat resting on a drifted fence row. Underneath, he found a head looking at him."

"Can I give you a ride into town?" the motorist asked. "Thanks, but I'll make it on my own," was the reply, "I'm on my horse." Newspaper editors could find something to joke about too."

"When better dust storms are made," the Dodge City Globe boasted, "the Southwest will make them." But us children especially hard to keep down. For us, the storms always meant adventure, happy chaos, a breakdown of teachers' authority, security, and maybe Daddy would make his favorite home-made chocolate candy. When darkness descended, as it did that April, humor, bravado, or a childlike irresponsibility had more value than a storm cellar. So, for all my long life I've enjoyed, sinfully by local standards, a good storm even if it is dust. And I've sure taken a lot of good natured banter about it too."

"In early 1936, Mother's continued experiments to reduce the dust proved that a large garden water sprinkler turned up high and set on loaded 55 gallon gasoline drum up-wind from the house washing a large part of the dust out of the air before it hit the walls. Additionally, the water splattered against our home and the resultant mud stopped up the cracks and crannies. Third, this moist air cancelled out the electrical charge of the dry particles before it could come into the house. Fourth, the wetted air that came in was dampish and smelled like rain, otherwise, the fine dust would hang suspended for the longest and moved with the slightest encouragement. But damp now, that dust stayed put! And mother had a "relatively" clean house. This may not sound momentous, but let me tell you it was a huge discovery and had significant consequences."

"Whether the storms brought laughter or tears, the dust that swept the plains in the 1930's created the most enormous environmental catastrophe in the entire history of man on this continent. In no other time or place had there been greater or more sustained damage to the ecology. And there have been few times when so much tragedy was thrust on its inhabitants. (Not even the Depression was as devastating.) And in ecological terms we have nothing in the continent's past that compares to it. In the decade of the 1930's, the sand storms of the Plains were a genuine unqualified disaster. Both financially and ecologically!"

"But the world hadn't been deforested yet, nor did we have the greenhouse effect or the ozone hole in those days either. Something to maybe make the dirty thirties seem like a Sunday School picnic. Only time will tell!

"These storms rolled serenely out of the north, the cold winds sliding under the warmer air, lifting up the turbulent face of the storm in huge cloud-like rolls, until they hit. This one did too! It came as soundlessly as a ghost, as relentless as death until its towering dust overrode us."

"As it silently covered the sky curling south, we "chickened out" and ran for cover, but by then we were "gone goslings". In that one instant it overwhelmed two little six year old girls and one eight year old boy and tumbled us along with the surging tumbleweeds. With our eyes muddied shut we barely found the porch steps before everything went solid black. Mother saw the afternoon light suddenly go dark and knew instantly what had us. She hit the porch light and came out, but she was as mad as an old wet hen, we hadn't the wisdom to come in ahead of the storm and she made Attila the Hun seem like Mary Magdalene. I understand now, her fear she couldn't find us in the dust, and she couldn't have."

"A few of our little friends couldn't find their homes in the dust so they just "stayed put 'till" the next day. My sister Mary remembers, as was usual, when some such catastrophe struck Daddy would be off on some eleemosynary mission. This time it was to Washington D. C. with several other Moore County farmers to plead with the Federal Government to stop foreclosing farm mortgages. Actually, my Dad, County Judge Noel McDade, and a couple of other farmer were astonishingly successful in their testimony and saved many a farmer from ruin."

"After 1935, the dust storms lost their drama for us children. We'd seen all that nature could throw. The storms were simply a burden to bare and bare it we did, but sometimes that burden was just about all we could bare. We though the whole world was like this and children everywhere simply lived with the environment."

"The plains people, however, then as now, were a tough minded, leather skinned bunch of prairie dogs. And not easily driven off. Even in 1935 we managed to laugh a bit at our misfortunes. The grown-ups told about the fellow who fainted when a drop of water struck him in the face and had to be revived by having a bucket of sand thrown over him. They also told the one about the motorist who came upon a ten-gallon hat resting on a drifted fence row. Underneath, he found a head looking at him."

"Can I give you a ride into town?" the motorist asked. "Thanks, but I'll make it on my own," was the reply, "I'm on my horse." Newspaper editors could find something to joke about too."

"When better dust storms are made," the Dodge City Globe boasted, "the Southwest will make them." But us children especially hard to keep down. For us, the storms always meant adventure, happy chaos, a breakdown of teachers' authority, security, and maybe Daddy would make his favorite home-made chocolate candy. When darkness descended, as it did that April, humor, bravado, or a childlike irresponsibility had more value than a storm cellar. So, for all my long life I've enjoyed, sinfully by local standards, a good storm even if it is dust. And I've sure taken a lot of good natured banter about it too."

"In early 1936, Mother's continued experiments to reduce the dust proved that a large garden water sprinkler turned up high and set on loaded 55 gallon gasoline drum up-wind from the house washing a large part of the dust out of the air before it hit the walls. Additionally, the water splattered against our home and the resultant mud stopped up the cracks and crannies. Third, this moist air cancelled out the electrical charge of the dry particles before it could come into the house. Fourth, the wetted air that came in was dampish and smelled like rain, otherwise, the fine dust would hang suspended for the longest and moved with the slightest encouragement. But damp now, that dust stayed put! And mother had a "relatively" clean house. This may not sound momentous, but let me tell you it was a huge discovery and had significant consequences."

"Whether the storms brought laughter or tears, the dust that swept the plains in the 1930's created the most enormous environmental catastrophe in the entire history of man on this continent. In no other time or place had there been greater or more sustained damage to the ecology. And there have been few times when so much tragedy was thrust on its inhabitants. (Not even the Depression was as devastating.) And in ecological terms we have nothing in the continent's past that compares to it. In the decade of the 1930's, the sand storms of the Plains were a genuine unqualified disaster. Both financially and ecologically!"

"But the world hadn't been deforested yet, nor did we have the greenhouse effect or the ozone hole in those days either. Something to maybe make the dirty thirties seem like a Sunday School picnic. Only time will tell!